Gilberto Gil with the Filhos de Ghandi afoxé during Carnaval in 2009.

Every year, an estimated two million celebrants crowd Salvador Bahia . Linda Yudin is a dance ethnologist, co-director of the Viver Brasil dance company in Los Angeles , and a teacher of Brazilian dance at Santa Monica College

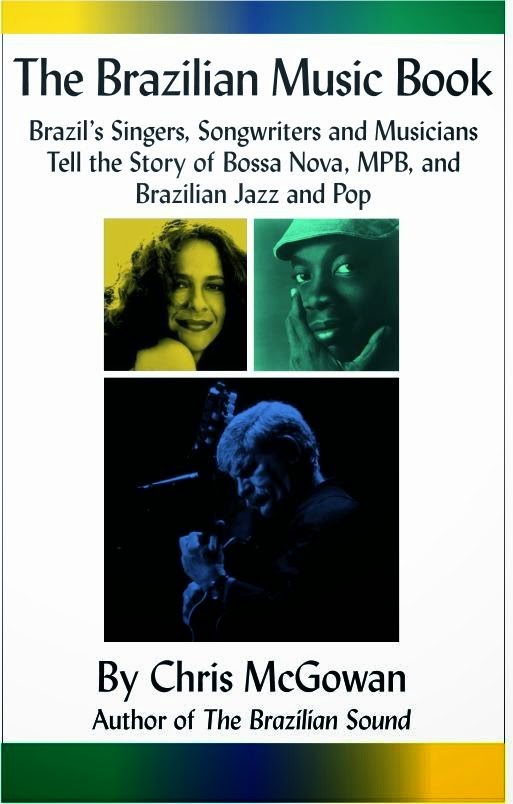

--Chris McGowan

--Chris McGowan

Kirk: I would tend to agree with Linda. The number of major blocos has not changed in recent years. The 'flagship' organizations still have the same status. Additionally however, during Carnaval there are a number of lesser known organizations that do participate, in some cases, as neighborhood spin-offs of the major ones. There are also other organizations that serve kids, just like the mirim [children’s] groups of Ilê and Olodum. Finances are a serious issue. For this reason, this year Olodum cut its size in half (4,000 to 2,000 foliao [participants] and, 200 drummers to 100 - I was extremely fortunate to have made the cut!. Also, I heard a rumor that next year some groups might go down to 60 drummers equipped with wireless mics. The function of both the blocos and afoxés remains the same as before: to continually assert the cultural presence, relevance and vitality of the Afro-descendants (their local audience). While the afoxés are not political, the blocos are, due to their concerns with resistência cultural [cultural resistance] issues such racism, education, employment, etc. Yet at the same time, the blocos wish to reach an international audience that may or may not share, understand, or be interested in their fight. And it is this international consumer that the government is also interested in.

Chris: How has the music changed?

Chris: Has there been a permanent alteration in

Linda: I think that the the blocos afro and afoxés permanently marked Salvador's culture with a contemporary music and dance form that has been recognized world wide and that honors its African roots, yet fluidly blends the influences of other music forms from around the world. Bahian musicians and dancers too have much more access and chances to interface with other styles of great music that have come to Bahia because of international summer music festivals, tourists coming to Bahia to study Afro-Brazilian culture (and they too bring their own cultural traditions to share), and of course the internet has allowed for complete access to the world.

Kirk: Yes, because what was once shunned, or even illegal, is now mainstream. Originally, [Filhos de] Gandhi members were afraid to parade those first years because of police repression, but today they are celebrated for their message. Before Ilê, no one presented African-oriented themes in the street, now it is commonplace. Their Beleza Negra [Black Beauty] festival celebrates this question of black aesthetics, and its value/contribution to society. The 'samba reggae' movement has therefore been much more than a mere beat. Its repercussions (pun intended) have impacted fashion, food, dance, language, and political consciousness locally and internationally. Chris: Any other comments?

This discussion took place in May, 2007. The revised, 3rd edition of The Brazilian Sound is available on Amazon.com and Barnesandnoble.com worldwide.

© Chris McGowan 2009.

2 comments:

Uma das melhores passagens do carnaval da Bahia, muinta saudade para uma brasileira que mora sozinha no fim do mundo americano.

deixa eu ver a minha Bahia, minha raiz, meus blocos, minha cultura.Me manda foto do Araketu e do olodum, Ile aye, muzenza e todos que fazem a musica mais bonita do Brasil....

Post a Comment